200,000+ products from a single source!

sales@angenechem.com

Home > Cyclic Hypervalent Iodine Reagents: Enabling Tools for Bond Disconnection via Reactivity Umpolung

Cyclic Hypervalent Iodine Reagents: Enabling Tools for Bond Disconnection via Reactivity Umpolung

Durga Prasad Hari,† Paola Caramenti,† and Jerome Waser*

Laboratory of Catalysis and Organic Synthesis, Ecole Polytechnique Fedé rale de Lausanne, EPFL SB ISIC LCSO, BCH 4306, 1015 ́

Lausanne, Switzerland

1. INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT

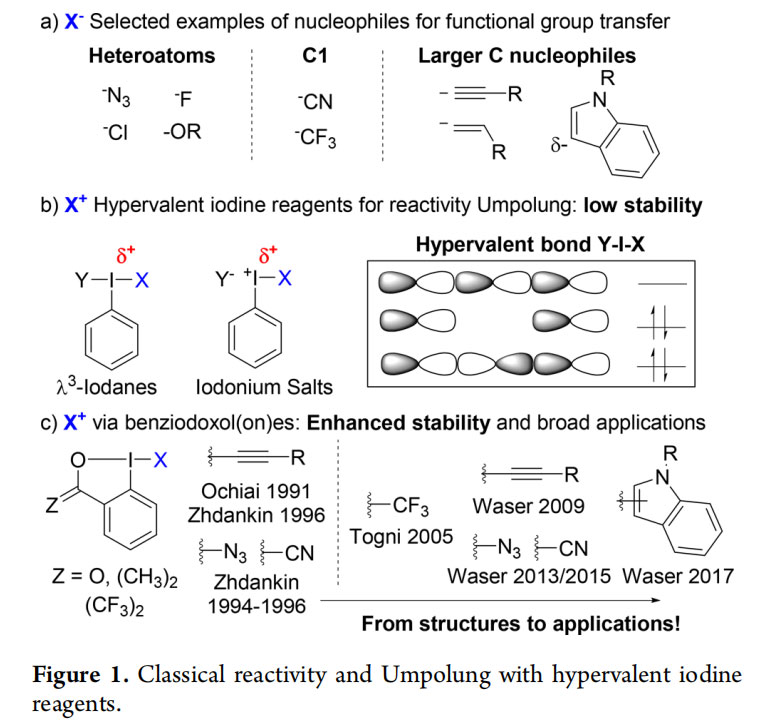

Organic compounds have a deep impact on our everyday life as drugs, agrochemicals, or materials. Over the last century, organic synthesis has matured as a craft and a science. Guidelines have been conceptualized to harness the fundamental properties of atoms, such as their electronegativity, to select adequate disconnections for bond formation.1 For example, functional groups containing electronegative atoms, such as nitrogen, halogens, oxygens, or sp2 and sp3 hybridized carbons, are best introduced as nucleophiles onto the carbon skeleton of organic compounds (Figure 1a). This approach is highly successful, but does not allow chemists to make all disconnections, as nucleophilic positions cannot be functionalized. To extend the versatility of organic synthesis, Seebach has introduced the concept of Umpolung (reversal of reactivity):2 If the innate reactivity of synthons can be inverted, new disconnections become possible, leading to greater diversity and synthetic

efficiency.

In this context, hypervalent iodine reagents have taken a privileged position based on the work of pioneers such as Beringer, Koser, Valvoglis, Moriarty, Zhdankin, Kita, Ochiai, and many others (Figure 1b).3 Both iodanes and iodonium salts allow the Umpolung of many nucleophiles into electrophilic synthons. Even if the concept of hypervalency is still a subject of controversy,4 it has been successfully used to rationalize the exceptional properties of hypervalent iodine reagents. However, their high reactivity can also lead to instability in the presence of strong bases, transition metals or when heating. In this context, benziodoxol(on)es (BX, Figure 1c), a class of cyclic hypervalent iodine reagents, have shown increased stability due to the inclusion of the iodine atom into a heterocycle.5,6 In particular, the groups of Ochiai and Zhdankin successively reported stable ethynyl (EBX),7,8 azido (ABX),9 and cyano (CBX)10 benziodoxol(on)es. A further advantage of BX reagents is the modulation of their reactivity through the trans-effect in the hypervalent bond.11 Derivatives bearing carboxy, isopropyl, and hexafluoroisopropyl substituents have been most broadly used.

For many years, structural studies on benziodoxolones have dominated the field, with few attempts in developing new synthetic applications. The situation changed in 2006, when Togni and co-workers reported the use of benziodoxol(on)es for trifluoromethylation.12 The so-called Togni reagents are now broadly used for the introduction of pharmaceutically relevant trifluoromethyl groups on organic compounds.13 Since 2008, our group has explored the potential of other BX reagents for group transfer reactions. We demonstrated that this class of reagents constitutes a unique toolbox for synthetic chemistry, which are superior to simple iodonium salts in many direct, transition metal- and photoredox- catalyzed transformations.

After having focused on electrophilic alkynylation,14 we moved to azidation and cyanation. In 2017, we introduced a new class of benziodoxolone reagents for the Umpolung of electron-rich heterocycles, in particular indoles and pyrroles. Many other groups have since then used BX compounds in group-transfer reactions.15,16 Herein, we will present an overview of our 10 year journey in the fascinating reactivity of these reagents

2. ELECTROPHILIC ALKYNYLATION

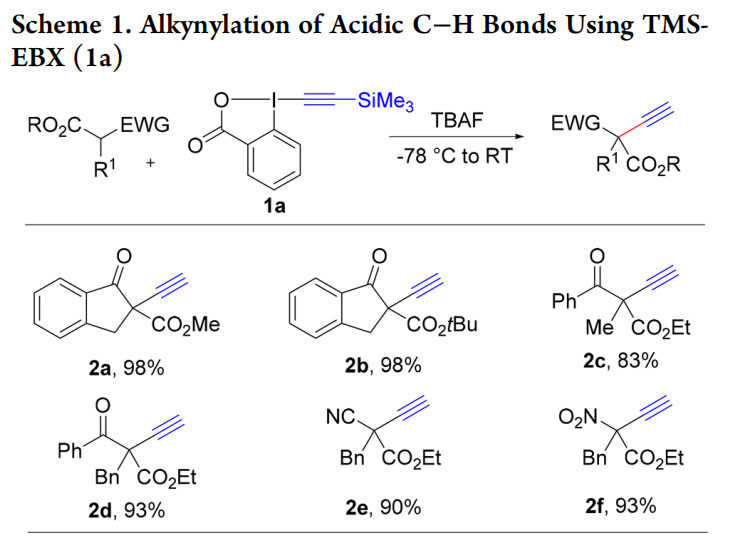

2.1. Alkynylation of Acidic C−H Bonds

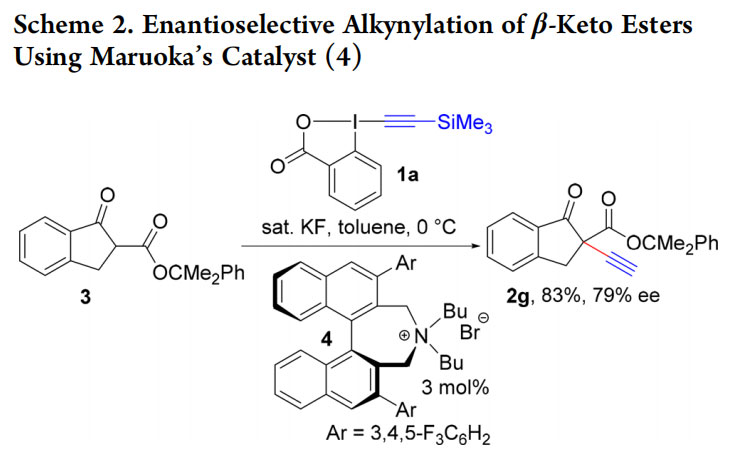

We first encountered EBX reagents in 2010, when using alkynyliodonium salts for the alkynylation of enolates using reported methods.17,18 We were facing serious issues of reproducibility and were not able to induce enantioselectivity under phase-transfer conditions. Building on the higher stability of EBX reagents,7,8 we successfully used TMS-EBX (1a) and TBAF with stabilized enolates to give terminal alkynes 2a−f in excellent yields (Scheme 1).19 Asymmetric induction was now possible using Maruoka’s phase transfer catalyst (4) (Scheme2).

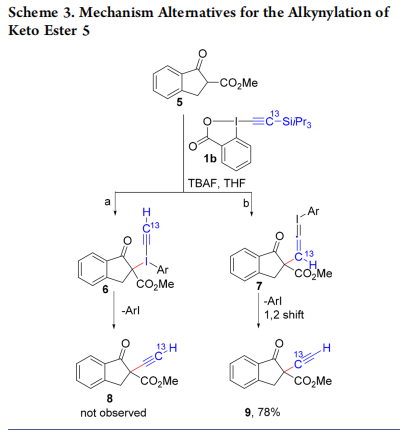

Two mechanisms can be envisaged (Scheme 3): Addition−elimination on the iodine atom (a) or conjugate addition to the alkyne, followed by reductive elimination and 1,2 shift (b). The use of 13C-labeled reagent 1b led to product 9, 19 which is in agreement with the 1,2 shift pathway.17,18

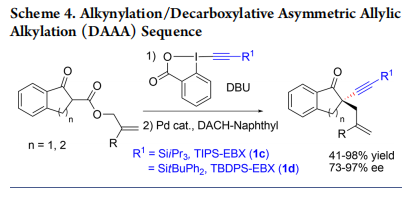

In 2014, as the phase-transfer approach was limited in both scope and enantioselectivity, we reported an alternative strategy to access quaternary stereocenters: Racemic alkynylation, followed by an enantioselective Tsuji−Trost allylation (Scheme 4).

2.2. Alkynylation of Heteroatoms

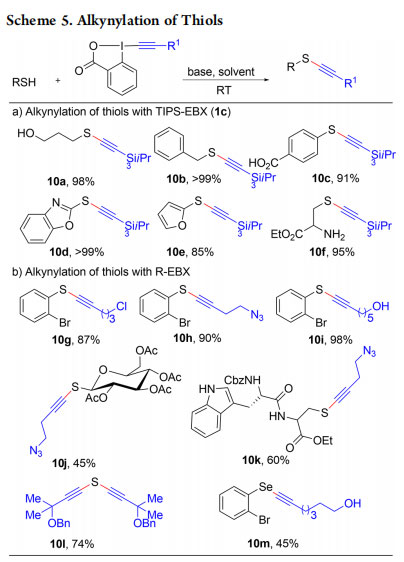

In 2013, we wondered if EBX reagents could also contribute to a more efficient synthesis of thioalkynes. These compounds are usually synthesized by addition of acetylides to oxidized thiol precursors.22 Whereas only disulfides were obtained when the alkynylation was attempted with alkynyliodonium salts, a quantitative yield was realized using TIPS-EBX (1c) (Scheme 5).23,24 The reaction proceeded in 5 min at room temperature in an open flask with a wide range of EBX reagents and thiol or selenol substrates (products 10a−m).

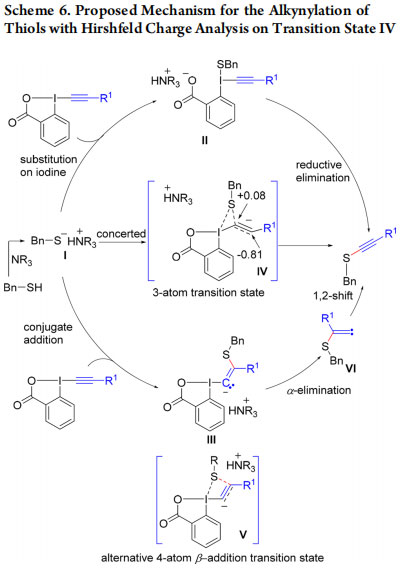

A mechanism for the thiol-alkynylation reaction was proposed based on computational studies (Scheme 6).24 First, thiolate I could attack on the iodine atom of EBX to give II, which then undergoes reductive elimination to give the product. However, intermediate II was not observed in the computational studies.

As an alternative, conjugate addition of thiolate I to give vinyl benziodoxolone III, which undergoes α-addition followed by 1,2 shift, leads to the product. This pathway was observed with a transition state energy of 23 kcal/mol. Nevertheless, a concerted pathway via asynchronous transition state IV with significant Hirshfeld charge separation was identified with a lower energy of 10.8 kcal/mol. In 2015, we further identified a four-atom transition state V leading to β-addition, which is favorable for alkyl groups on EBX, whereas α-addition is favored for electron withdrawing groups.25

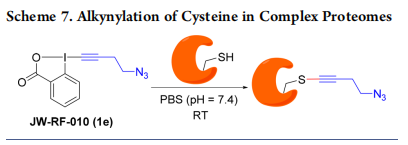

The very fast and selective reaction of EBX reagents with thiols under mild conditions motivated us to investigate applications in chemical biology. In 2015, Adibekian and our group reported a method for proteomic profiling of enzymes with hyperactive cysteines in living cells by using the azidesubstituted EBX JW-RF-010 (1e) (Scheme 7).26 The utility of the method was further demonstrated by identifying one target of curcumin in HeLa cells.

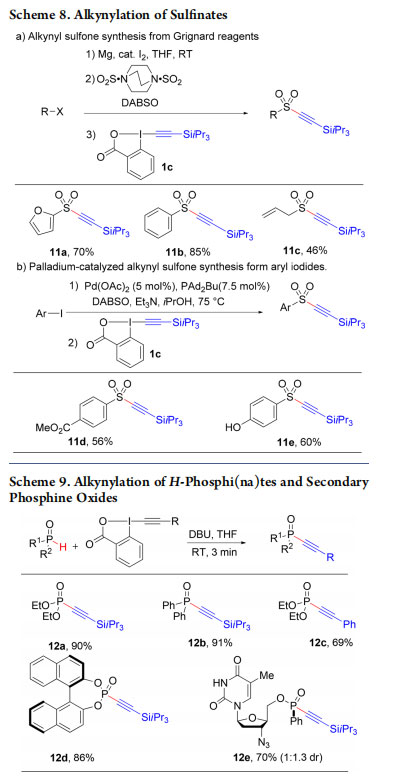

As a last effort in the area of heteroatom functionalization, we further demonstrated the use of EBX reagents for the alkynylation of other sulfur and phosphorus nucleophiles. Sulfones 11a−e were obtained from Grignard reagents or aryl iodides using DABSO (diazabicycloctane bis(sulfur dioxide)) as sulfur source (Scheme 8) 27 and alkynyl phosphorus derivatives 12a−e were synthesized from H-phosphi(na)tes and secondary phosphine oxides (Scheme 9).28

2.3. C−H Alkynylation of Hetero(arenes)

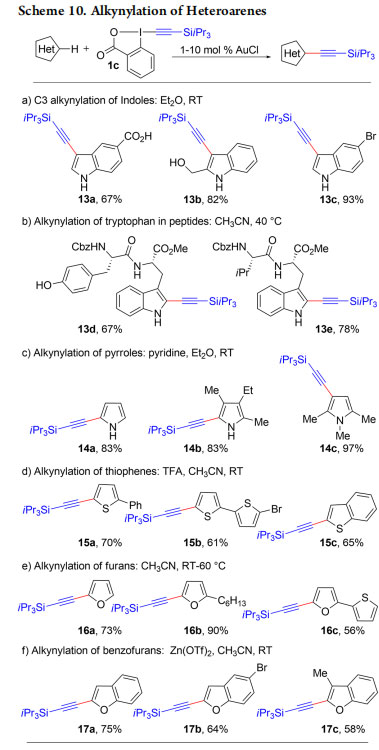

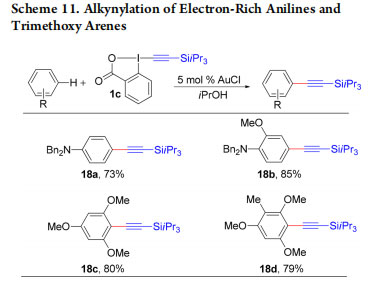

Our research on EBX reagents with simple nucleophiles had been highly successful, and we wondered if they could be also applied in the more complex settings of transition metal catalysis. Since 2007, using alkynyliodonium salts, C−H functionalization had been a major project in our group, but without success, as the sensitive reagents constantly decomposed in the presence of the metal catalyst. In 2009, we had our first success with the direct alkynylation of indoles using TIPSEBX (1c) and AuCl as catalyst (Scheme 10a).29 C3 alkynylated indoles 13a−c were obtained in good yields. The formation of C2-alkynylated indoles was observed when the C3 position was blocked (Scheme 10b, products 13d,e).30,31 The direct C−H alkynylation reaction was further extended to pyrroles (Scheme 10c, products 14a−c),32 thiophenes (Scheme 10d, products 15a−c),33 furans (Scheme 10e, products 16a−c),34 benzofurans (Scheme 10f, products 17a−c),35 and anilines and trimethoxy arenes (Scheme 11, products 18a−d).36

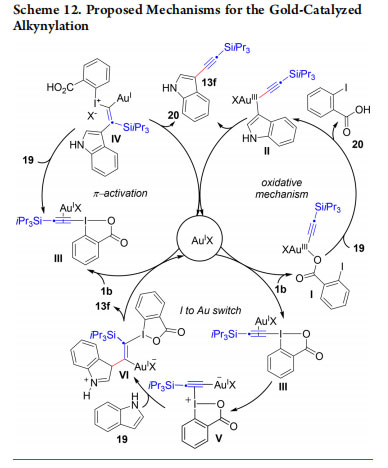

Initially, we hypothesized two mechanisms involving either an oxidative mechanism or a π-activation for the C−H alkynylation (Scheme 12).32 Oxidative addition of EBX on Au(I) would give Au(III) intermediate I. Electrophilic auration leads then to II and reductive elimination gives 13f. The π-activation involves coordination of Au(I) to the triple bond to give III, followed by nucleophilic attack leading to IV. Finally, α-elimination followed by 1,2-shift gives 13f. No silicon-shift was observed when C13 labeled reagent 1b was used. This result supports the oxidative mechanism. However, Ariafard found by computations that both the oxidative and π-activation mechanisms were too high in energy and proposed a iodine to gold shift on the alkyne to give intermediate V. 37 Indole addition to V, followed by β- elimination and rearomatization would lead to 13f. Common to the three mechanisms is an electrophilic aromatic substitution step, which explains the high regioselectivity observed. In 2013, we also reported a palladium-catalyzed selective C2 alkynylation.38 Other research groups later demonstrated that EBX reagents can be used for C−H alkynylation using a broad range of transition metal catalysts.16

2.4. Alkynylation Involving Domino Reactions

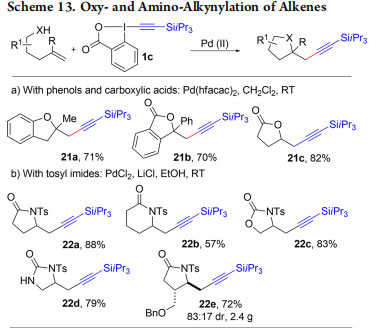

In our work on heterocycles, we had demonstrated that EBX reagents could be used for a single sp2−sp bond formation. We then investigated their use in domino reactions leading to the alkynylation of sp3 centers. We reported the first example of such a transformation with the palladium-catalyzed intramolecular oxy- and amino-alkynylation of olefins using phenols, carboxylic acids, and imides as nucleophiles (Scheme 13, products 21, 22).39,40

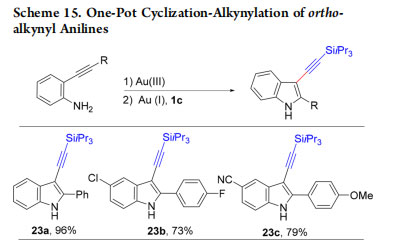

Initially, we proposed a mechanism involving a Pd(IV) intermediate II (Scheme 14).39 Oxy/aminopalladation of the olefin gives intermediate I, which undergoes oxidative addition with TIPS-EBX (1c) to give II, followed by reductive elimination. Ariafard proposed a different mechanism involving formation of palladium allenylidene intermediate III (in equilibrium with the iodine bound alkynyl palladium complex IV) based on computational studies.41 1,2-Shift followed by β- elimination of 2-iodobenzoic acid leads to the product. We then wondered then if domino processes could be also used for the synthesis of alkynylated heterocycles not accessible via C−H functionalization. As a proof of concept, we realized a one-pot synthesis of C3-alkynylated indoles 23a−c upon reaction of anilines with TIPS-EBX (1c) using a gold catalyst (Scheme 15).42

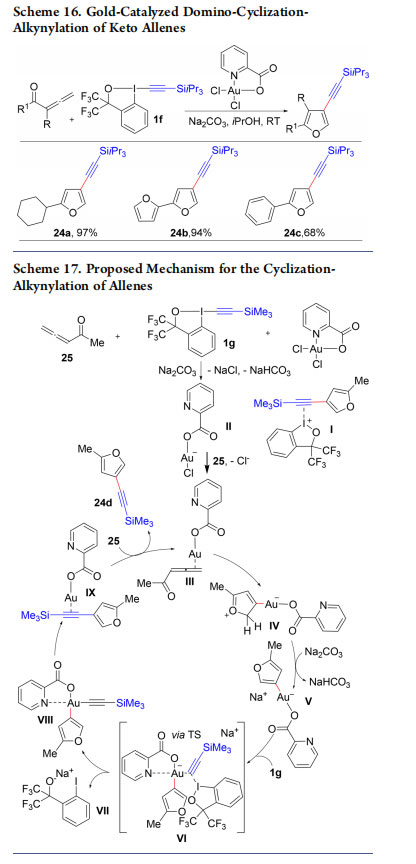

Nevertheless, such compounds can also be accessed via C−H functionalization. Therefore, we studied, in 2013, the dominocyclization-alkynylation of keto allenes into alkynyl furans using Au(III) picolinate as catalyst (Scheme 16).34 C3 alkynylated furans 24a−c were obtained in 68−97% yield, whereas C2 alkynylated furans are formed via C−H functionalization. In 2017, the reaction mechanism was studied by computational chemistry in collaboration with the Ariafard group (Scheme 17).43 Allene 25 first reacts with 1g and Au(III) to give iodonium I and Au(I) complex II. The latter then reacts with allene 25 to give III. Cyclization to IV followed by deprotonation with Na2CO3 gives V. Oxidative addition on V leading to VII and VIII is accelerated by the interaction of Au with the nitrogen atom (transition state VI). Au(III) complex VIII undergoes reductive elimination followed by ligand exchange with allene 25 to give product 24d and close the catalytic cycle. These interesting results showed that the Au(III) complex was only a precursor of the active Au(I) catalyst.

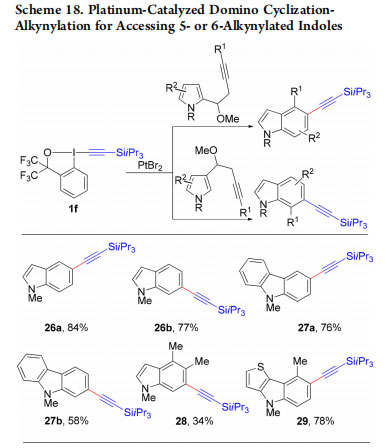

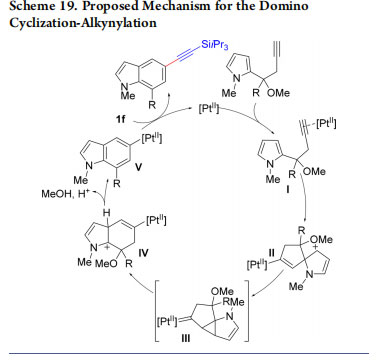

In 2015, we demonstrated that this strategy could also be used for the synthesis of indoles and carbazoles 26−29 alkynylated on the benzene ring (Scheme 18).44 This platinum-catalyzed process started from from 2- or 3-substituted homopropargylic pyrroles. The reaction probably proceeds via activation of the triple bond by platinum to give I (Scheme 19). Intramolecular attack of the most nucleophilic pyrrole C2 position gives then II. 1,2-Shift of the vinyl-platinum substituent via platinum carbene III then leads to IV. Finally, elimination of methanol and rearomatization gives platinum aryl complex V, which then reacts with 1f to deliver the product. In 2017, this mechanism was confirmed by Bi and co-workers based on computation.45

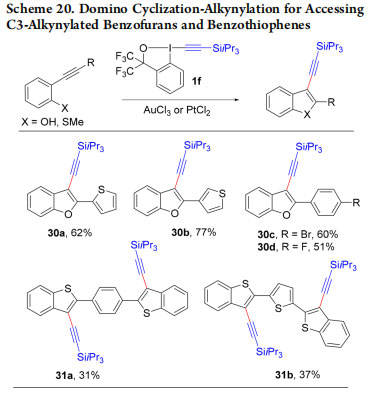

Highly conjugated hetereocycles are especially interesting as organic materials. In 2017, we used our strategy for the synthesis of C3-alkynylated benzofurans 30a−d and benzothiophenes 31a,b (Scheme 20).46 The obtained alkynylated heterocycles were efficiently transformed into heterotetracene building blocks for organic materials.

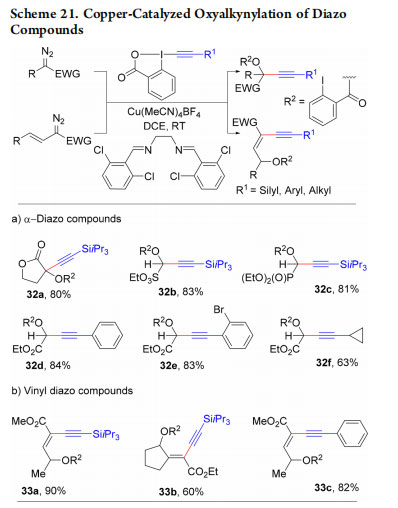

Alkynylation using EBXs usually releases 2-iodobenzoic acid. In 2016, we developed a copper-catalyzed oxyalkynylation of diazo compounds, in which the acid is incorporated in products 32a−f (Scheme 21a).47 When vinyl diazo compounds were used, enynes 33a−c were obtained as single geometric isomers(Scheme 21b). This example also demonstrates that the use of EBX reagent is not limited to precious metal catalysts, such as gold, platinum, or palladium.

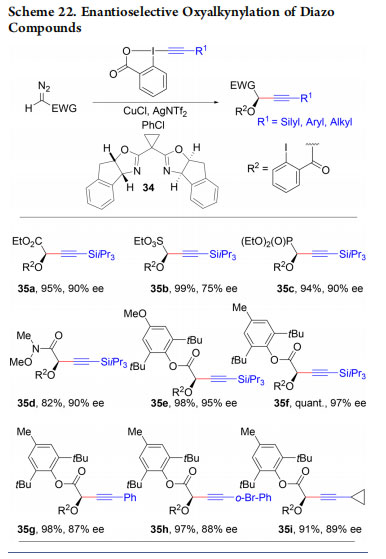

In 2017, we reported the enantioselective oxyalkynylation of diazo compounds using a copper catalyst and bisoxazoline (BOX) ligand 34 (Scheme 22, products 35a−i).48 Due to the high acidity of the propargylic hydrogen, these compounds cannot be accessed in enantiopure form via the addition of organometallic reagents onto the corresponding carbonyl compounds.

2.5. Alkynylation of Carbon Radicals

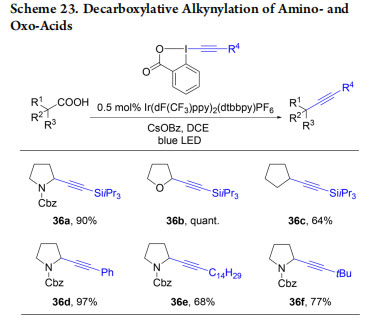

EBX reagents are highly useful for the functionalization of carbon and heteroatom nucleophiles, as well as organometallic intermediates. The functionalization of radicals, which can be generated under neutral conditions, constitutes a further interesting area of applications. Li and co-workers were the first to report a decarboxylative alkynylation of carboxylic acids using EBX reagents and strong oxidants.49 In 2015, we developed milder conditions for the synthesis of alkynes 36a−f based on photoredox catalysis to avoid strong oxidants(Scheme 23).50 Xiao and co-workers reported a similar transformation simultaneously.51

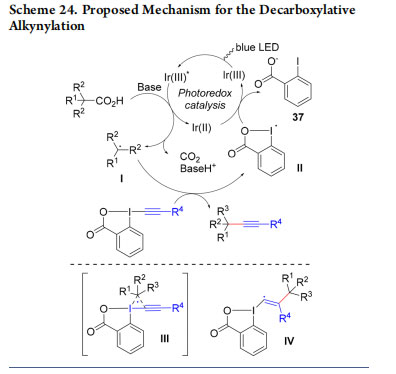

A mechanism for the decarboxylative alkynylation was proposed based on both experimental and computational studies (Scheme 24).52 Single-electron oxidation of the carboxylate by the excited state of the Ir(III)-catalyst generates radical I after extrusion of CO2. Addition to EBX then delivers the desired product and iodo radical II, which can then be reduced by Ir(II) to close the catalytic cycle. Concerning the radical addition step, two mechanisms very close in energy were proposed based on DFT calculations: a concerted α-addition via III or a β-addition via IV.

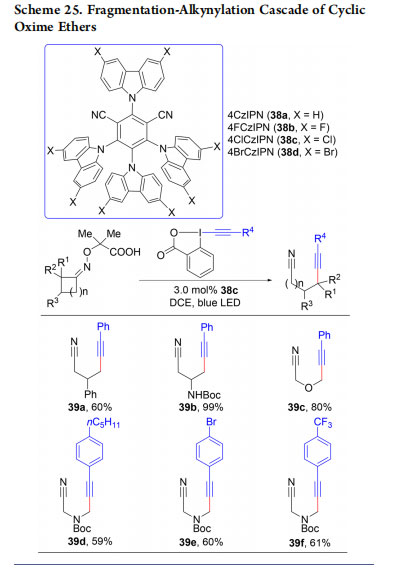

In 2018, we reported the alkynylation of nitrile-substituted alkyl radicals generated via oxidative ring fragmentation of cyclic oxime ethers (Scheme 25).53 The use of organic dye 38c with an increased reduction potential in the excited state compared to 4CzIPN (38a) led to the efficient fragmentation of both 4- and 5-membered cyclic oxime ethers to give the corresponding alkynylnitriles (39a−f). The reaction probably starts with the oxidation of the carboxylate by the excited photocatalyst. Fast decarboxylation followed by acetone extrusion leads to an imine radical. Fragmentation to an alkyl radical followed by alkynylation then gives the product.

3. ELECTROPHILIC AZIDATION

Azides, as alkynes, are versatile functional groups, which are usually introduced as nucleophiles. Electrophilic azide sources allow other disconnections. Noncyclic azide hypervalent iodine reagents are not stable and need to be prepared in situ. An important progress was realized when stable cyclic ABXs were introduced by Zhdankin and co-workers.9 Nevertheless, new synthetic applications emerged only in 2013, with the independent reports of Gade and co-workers,54 our group,55 and Studer and co-workers.56 Since then, the field is in full expansion.16

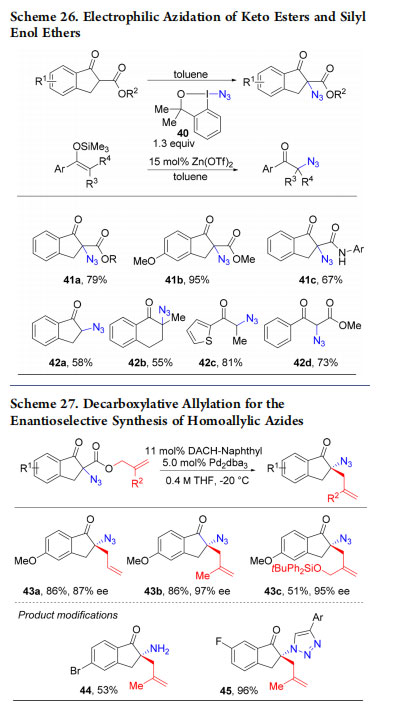

3.1. Azidation of β-Keto Esters and Silyl Enol Ethers

In 2013, we investigated the azidation of ketoester-derived enolates with ABXs as a proof-of-concept transformation. Such azidation had been realized with other hypervalent iodine reagents,57 but had not been reported with ABXs when we started our investigations. A metal free protocol for cyclic indanones was developed using azidobenziodoxole 40 (41a−c, Scheme 26).55 However, less reactive substrates such as silyl enol ethers and noncyclic keto esters did not react with 40. In this case, activation of the reagent with zinc triflate as catalyst was necessary to give products 42a−d. In parallel to our work,

Gade and co-workers reported an efficient enantioselective azidation of ketoesters using reagent 40. We then reinvestigated the Tsuji−Trost approach on allyl β-keto esters (Scheme 27). Homoallylic azides 43a−c were obtained in good yields and excellent enantioselectivities.58

Staudinger reduction and 1,3 cycloaddition gave then homoallylic amine 44 and triazole 45.

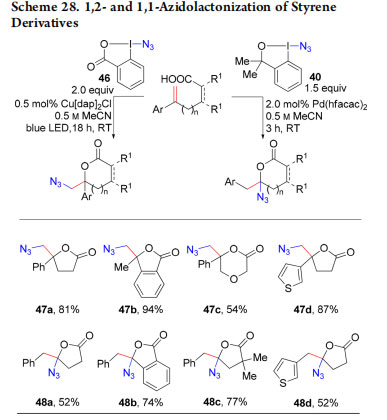

3.2. Generation of Azido Radicals: Azido-Lactonization and Ring Expansion

In 2017, our group became interested in using azidobenziodoxol(on)es reagents for the azido-lactonization of styrene derivatives in the context of extending the olefin functionalization reactions developed with oxyalkynylation (Scheme 28).59 Photoredox activation of ABX 46 (Zhdankin reagent)9 resulted in formation of an azido radical,56,60 which reacted with the styrenes to form 1,2-azidolactones 47a−d. No radical was formed from the weaker oxidizing 40. In this case, the use of Pd(hfacac)2 as Lewis acid gave 1,1-azidolactones 48a−d, probably via a iodination, 1,2-aryl shift, azidation sequence, highlighting again the possibility to finely tune the reactivity of EBX reagents.

Following an accident due to the explosion of a sample of ABX 46, we investigated its safety profile in collaboration with a specialized company, and discovered that it is both shock and friction sensitive.61 However, the more stable azidobenziodazole 49 (ABZ) could also be used for the generation of radicals under photoredox conditions in a new ring-expansion process to give cyclopentanones 50a−d (Scheme 29), as well as in reported azidative transformations.61

4. ELECTROPHILIC CYANATION

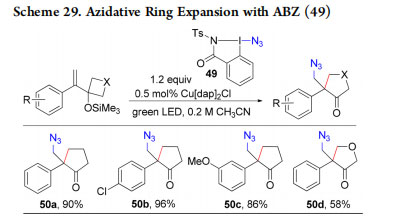

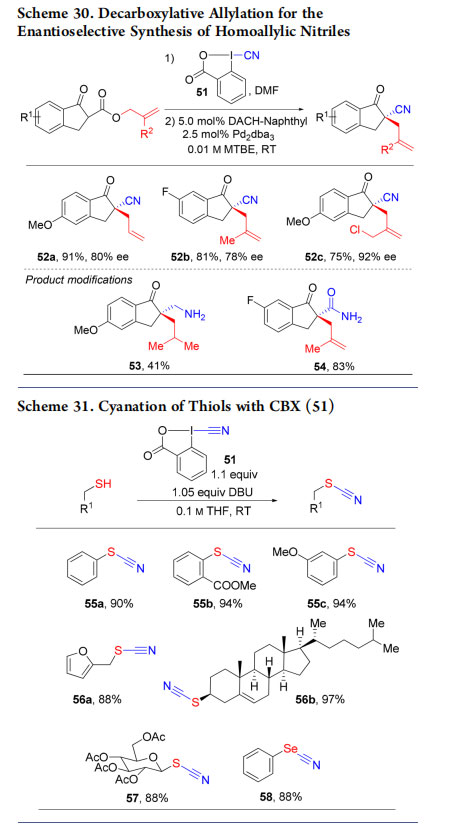

4.1. Synthesis of Homoallylic Nitriles

As for alkynes or azides, we expected CBXs10 to serve as electrophilic cyanide sources. In fact, CBX (51) could be used for the cyanation of allylic β keto esters, which were engaged in an enantioselective Tsuji−Trost process (Scheme 30, products 52a−c).58 The nitrile group could be then either reduced to amine 53 or hydrated to amide 54.

4.2. Synthesis of Thiocyanates from Thiols

Inspired by our results in thio-alkynylation (Scheme 5), we reported the use of CBX (51) for the cyanation of thiols (Scheme 31).62 Aromatic and aliphatic thio- and selenocyanates 55−58 were obtained in excellent yields. Interestingly, hypervalent sulfur reagents were later developed by Alcarazo and coworkers to perform similar reactions.63

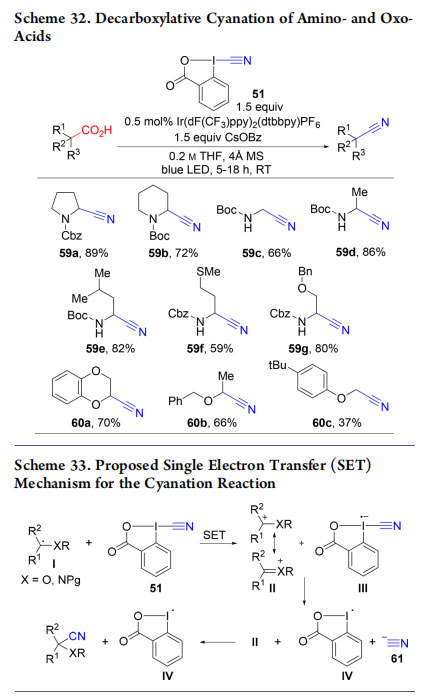

4.3. Decarboxylative Cyanation of Carboxylic Acids

Our work in the photoredox-catalyzed decarboxylative alkynylation was extended to decarboxylative cyanation using CBX (51) to give nitriles 59 and 60 (Scheme 32).52 In contrast to alkynylation, cyanation was shown through experiments and DFT calculations to proceed via carbocationic intermediates (Scheme 33). CBX (51) being a stronger oxidant than EBX (1), it is able to oxidize radical I, formed under

photoredox conditions, to give stabilized carbocation II and radical anion III (single electron transfer, SET). The latter collapses into radicalIV and cyanide anion (61). Recombination of II and 61 gives the product, whereas IV can re-enter the photoredox cycle (Scheme 24).

5. ELECTROPHILIC INDOLES AND PYRROLES

5.1. Synthesis of New Indole and Pyrrole BX Reagents

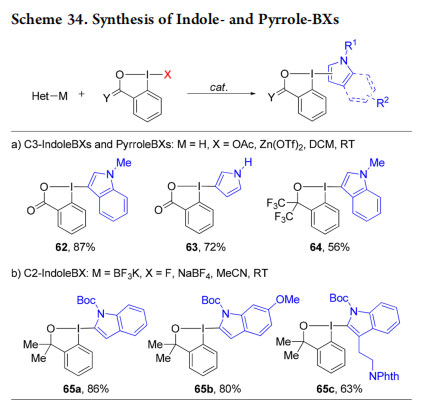

In 2017, we reported the serendipitous discovery of a novel class of stable cyclic indole- and pyrrole-based BX reagents.64−66 C3-substituted-indole and pyrrole BX reagents 62−64 were accessed from the heterocycles by the Lewis acid catalyzed addition to acetoxybenziodoxol(on)es (Scheme 34a).64,65 C2-substituted indole BX reagents 65a−c were obtained by reaction of trifluoroborate salts with fluorobenziodoxole (Scheme 34b).66

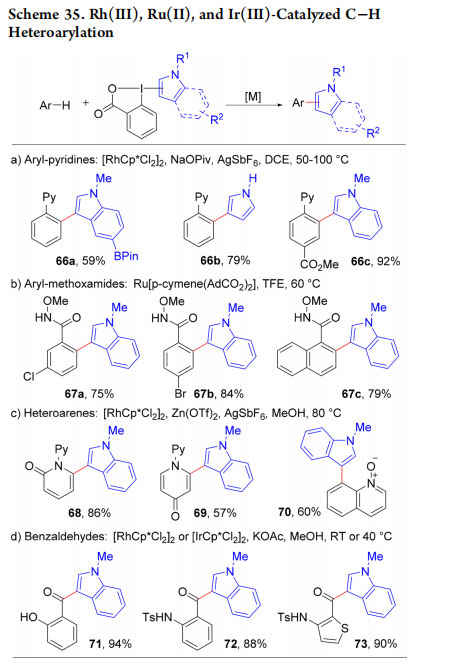

5.2. Metal-Catalyzed C−H Functionalization with IndoleBXs and PyrroleBXs

In most metal-catalyzed C−H arylation processes, electron-rich heterocycles are used as nucleophilic partners, leading often to regioselectivity and reactivity issues. Our electrophilic reagents allowed an Umpolung approach in the Rh(III)- and Ru(II)- catalyzed directed C−H functionalization of arenes (Scheme 35a,b). The desired heteroarylated products were obtained in good yields as single regioisomers using either pyridine (66a−c) or methoxamide (67a−c) directing groups.64,65 Heteroarylated 2- and 4-pyridones 68 and 69 and quinoline N-oxide 70 could also be accessed (Scheme 35c).67 Finally, the method could be extended to ortho-hydroxy and amido benzaldehydes using either a Rh(III) or an Ir(III) catalyst (Scheme 35d, products 71−73).68 None of these transformations was successful using the corresponding aryl iodides or iodonium salts.

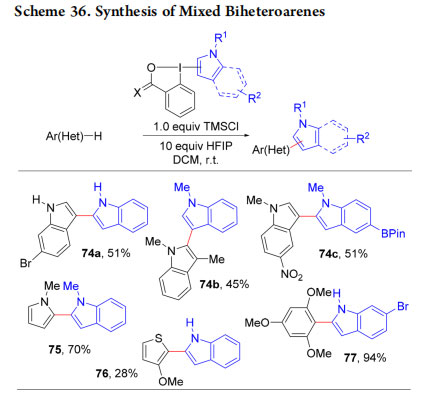

5.3. Metal-Free Oxidative Cross-Coupling for the Synthesis of Mixed Biheterocycles

In 2018, we reported a metal-free oxidative cross coupling using TMSCl and HFIP as activators for the synthesis of mixed biindoles 74a−c and other mixed heteroaryls 75−77 (Scheme 36).66 This method allowed the synthesis of biheterocycles with complete regioselective installation of functional groups in either one of the two reacting partners. The reasons for the exclusive transfer of the indole heterocycle and the observed high regioselectivity are not well understood at this stage and will require further mechanistic studies.

6. CONCLUSION

Since 2008, our group has exploited the reactivity of benziodoxol(on)es reagents in organic synthesis. The basis for this work had been set by synthetic and structural studies by pioneers in the field of hypervalent iodine chemistry, such as Martin, Ochiai, and Zhdankin among others. The potential of these reagents for fine chemical synthesis via “Umpolung disconnections” was first demonstrated extensively by Togni and co-workers in trifluoromethylation and our group in alkynylation. Our work on ethynylbenziodoxolone (EBX) reagents showed for the first time their exceptional properties in the electrophilic alkynylation of nucleophiles, radicals, and organometallic intermediates. We then demonstrated that azidobenziodoxolones (ABX) and cyanobenziodoxolones (CBX) were equally useful for electrophilic azidation and cyanation. Finally, we introduced new reagents for the Umpolung of indoles and pyrroles. Nowadays, many research groups around the world are using cyclic hypervalent iodine reagents to develop new transformations. The reason for the success of BX reagents may reside in the exceptional reactivity of hypervalent iodine, combined with the extra stability and modularity of the cyclic structure. We expect that the “synthetic treasure” of benziodoxol(on)es has just started to be exploited, and many more reagents and transformations still remain to be discovered。

■ AUTHOR INFORMATION

Corresponding Author

*E-mail: jerome.waser@epfl.ch.

ORCID

Jerome Waser: 0000-0002-4570-914X

Author Contributions

†

D.P.H. and P.C. contributed equally.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Biographies

Durga Prasad Hari received his master degree from IIT Madras and his PhD degree from the University of Regensburg under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Burkhard Koenig in 2014. He worked as postdoctoral fellow under the supervision of Prof. Jerome Waser at EPFL from 2014 to 2018. Currently, he is a postdoctoral fellow in the group of Prof. Varinder Aggarwal at the University of Bristol. His research interests

focus on applications of hypervalent iodine reagents in organic synthesis. He was a finalist of Reaxys PhD prize 2012.

Paola Caramenti received her Master degree in 2014 at Università Statale di Milano, under the guidance of Prof. Francesca Clerici. She then joined the group of Prof. Jerome Waser at EPFL to pursue her PhD

studies. Her current research topic involves the synthesis of novel hypervalent iodine reagents and their application. Jerome Waser studied chemistry at ETH Zurich (PhD degree in 2006 with Prof. Erick M. Carreira). He then joined Prof. Barry M. Trost at Stanford University as SNF postdoctoral fellow. From 2007 to 2014, he was an assistant professor at EPFL. Since 2014, he is associate professor at EPFL, focusing on the use of hypervalent iodine reagents in synthesis, cyclopropane chemistry and tethered reactions. He received the ERC starting (2013) and consolidator (2017) grants, the Werner prize of the Swiss Chemical Society 2014, and the Springer Heterocyclic Chemistry Award 2016.

■ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Swiss National Science Foundation (No. 200021_159920), the European Research Council (ERC Starting Grant 334840), and EPFL for financial support.

Organic compounds have a deep impact on our everyday life as drugs, agrochemicals, or materials:

© 2019 Angene International Limited. All rights Reserved.